Here we find our World War I and II themed poems, radio plays and stories. These works were originally published in 2018 and 2019 as an Armistice tribute on our website http://www.armisticetribute.org.au That website closed in August, 2020.

To directly access World War Radio Plays, scroll down

For direct access to our World War Stories, scroll down even further!

In 2022, we decided to accept all works on stories of military conflict, be they stories of World War I and II, or other conflicts, such as the Vietnam war.

All material on this page will still continue to be viewable, but no new entries will be added. All entries in this category published after 8 May 2022 will appear in ‘Military Conflict Stories‘

updated 16 May 2022

POEMS

Epilogue 1918

by John Aldous

Then

Time to come home

Time

Time to come home

To

To come home

Come

Come home

Home

Home

©John Aldous

********************************

Two Poppies

by Norah Dempster

Two old women at the War Memorial,

they take their time,

names on bronze panels stretch either side.

‘There he is,’ one whispers, and they both stand still.

Their mother’s only brother,

he fought at the Somme.

the one who never came home

Their childhood kitchen opens up:

coal stove, pots bubbling, table set,

milk jug, sugar, plates in place,

knives and forks nice and straight.

The clock ticks.

Then a smash at the door, Army boots flung,

milk jug tipped, their mother hit—

their father, swearing, back from the pub

still fighting the Japanese.

the one who came home

Two old women reach in their bags,

hold a poppy each, stand on their toes,

pin both poppies beside the first name.

©Norah Dempster, 2018

******************************

Sounds of War

by Colleen Dewis

Weary women weeping, children sleeping.Soldiers cursing, crying, praying, God-seeking.Wounded lying dying, sighing, trenches seeping.Bayonets, guns, bullets, bombs.Leaders meet to make a choice, heed the wise united voice.Sign! No winners, all rejoice At last the Armistice!

©Colleen Dewis, 2018

********************************

Haiku 1918

by Colleen Dewis

Aim to end this war

Killing maiming soon no more—Armistice in sight

©Colleen Dewis

*********************************

Flanders Fields 2018

by Geoffrey Dobbs

One hundred springs have cast their wreaths upon this land;

War’s jagged signature still scrawls across its fields,

Though faded now and blurred by time’s erasing hand.

Above, the larks still sing; below, the earth still yields

A brutal harvest: barbed wire, shells and nameless bones.

The bugle calls dissolve to silence amongst the lines

Of voiceless, tongueless dead, as mute as standing stones.

Subsumed within a vaster silence now, they lie

Bereft of present, past or future’s hopes and dreams.

What meaning now for them in polished bugle calls

Or politicians words?

For us alone it seems

The solemn Ode’s declaimed.

To us the duty falls:

Each year to say ‘Their names shall live for evermore;’

Oh, yes, maybe the names; but nothing, nothing more.

©Geoffrey Dobbs, 2018

**********************************

November Morning

by Jan Storey

A soldier sleeps shrouded by mist, blind to the

Rats fat on the flesh of fallen comrades. While

Military men in the Forest of Compiegne

Ink an agreement in a railway carriage to

Silence the guns and end the grim horror.

Then, that very same day at the eleventh hour

In damp November trench earth,

Cold troops slump in dazed disbelief

Each mad with thoughts of home.

©Jan Storey, 2018

*************************************

Courage

by Joy Meekings

Home is where the heart is, or that is what we say

But when you’re in a war zone your home’s so far away.

You think it’ll be an adventure, see the World, have some fun!

Since I’ve been in Gallipolli, all I want to do is run—

Away from death and dying, the blood, guts and gore.

I lost me best mate yesterday, I can’t take this any more!

The soldier standing next to me says close your eyes and think of home:

The sounds of war start to fade, as the Aussie Bush I roam;

I can smell eucalyptus trees and see the endless blue sky,

My mother’s face comes into view, God I don’t want to die!

Then my mother says to me: son, have courage, don’t give in,

You’ve never been a quitter, so be strong and you will win.

Now her face is fading, but her words are ringing true—

I’ll fight on for my best mate, he will get me through!

©Joy Meekings, 2018

***********************************

Never

by Joy Meekings

She was tending to her garden when the telegram came,

Little did she know her life would never be the same.

Such a small slip of paper stating that her son had died.

He had meant the world to her, she felt so dead inside.

She wanted to see him, hold him close against her heart,

Tell him how much she loved him, they’d no longer be apart.

Instead she stared at the telegram, tried to steady her feet,

She was starting to realise never again would they meet.

He was called a war hero, for bravely saving many men

But all his mother ever thought was ‘he won’t be home again.’

©Joy Meekings, 2018

************************************

Renewal

by Joy Meekings

The grass and flowers have disappeared from the fields that once had plenty

No children laughing, playing games, the fields lie blood-stained and empty.

A terrible battle was fought here, and many young Soldiers were lost

These fields sadly remind us, of what it really cost.

For those who survived the onslaught, their cities decimated,

There will be renewal one day, and their homes recreated.

All the fields will regenerate and become as they were before

But when will we ever learn, and find an alternative to War?

©Joy Meekings, 2018

**********************************

Gallipoli Mates

by Sandra Stirling

We hope you won’t hear us leaving

As we steal away at night,

We’ve left guns on rope to fire at will

As we stumble out of sight.

We hope that you, our brothers, know

We leave with a heavy heart,

That we couldn’t take you with us,

You, who were here at the start.

We know in the years that follow

We’ll return to the slopes we strode

to the trenches we crouched in a’tremble

That became our hellish abode.

For every memory we carry

In the years that lie ahead,

There won’t be a moment forgotten

That we, as comrades, shared.

And then when the Last Post is sounded

As it will for all of your mates,

We hope that you’ll hear us coming

And we’ll meet at those heavenly gates.

©Sandra Stirling, 2018

************************************

Gait

by Sandra Stirling

When the call went out one day, so many years ago,

The young men came from near and far to fight a foreign foe.

There were those who came with a country gait and often a friendly smile

Or a lifted hat and a ‘G’day, mate,’ as he walked his country mile.

With shoulders squared and eyes that see for miles around the land,

He’s happy to stop and chat a while and shake a neighbour’s hand.

And then there were those who liked to walk at a pace just that much quicker,

Who enjoyed the lights and picture shows that belonged to the city slicker.

In suit and cap, with a Gladstone bag, he smiles at the dawn’s new light,

Clanging trams and traffic flows for him a happy sight.

These young men then fought and crawled up cliffs of crumbling sand,

While bullets sprayed and gas destroyed these youngsters from our land.

And still once a year on Anzac Day, we remember them with pride,

The country boy and city lad now lying side by side.

©Sandra Stirling, 2018

**************************************

RADIO PLAYS

Listen to podcasts of our radio plays. Individual scripts are also available to follow the text of the radio plays, or for use by community groups to present their own play-readings. If using these plays, please recognise that the copyright is held by the authors listed, and make proper acknowledgement of the source of the play.

If you want to simultaneously hear the radio play and read the script at the same time, then follow these steps: With both desktop PCs and Macs, hold down the SHIFT key on your keyboard, and click the audio arrow and then the DOWNLOAD button for the written script

****************************************************************************************

world war 2

Ned’s Gift

A radio play by Juliet Charles

This radio play by Juliet Charles was adapted from the short story “Evening In Paris” by Michelle Deans, the copyright of which is held by Michelle Deans

Synopsis

A young man’s journey from boyhood on a rural orchard – where life seems blissfully simple and trouble-free, to manhood and the brutal realities of war. Amongst the obscenities of battle – cruelty, death and desperation, he encounters a simple act of kindness.

Cast and Production Credits

Cast:

| STANLEY | Justin Keyt |

| JIM | Stuart Anderson |

| GRANDSON | Jack Laragy |

| NED | Alex Ashcroft |

| MAGGIE | Juliet Charles |

Production Team:

| TECHNICAL DIRECTOR | Raymond Simms |

| DIRECTOR | Cheryl Threadgold |

To read the radio play script, please click DOWNLOAD below

To listen to an audio file of this play, click the arrow below on left

©Juliet Charles

***************************************************************************************

world war 2

A Pilot and a Nurse: Letters

A Radio Play by Juliet Charles

Adapted from the letters of Squadron Leader, Kenneth Pryce Wilson and the reminiscences of Betty Joy Wilson

Synopsis

They met on a tram in 1938, fell in love and became engaged. Then war interrupted their romance. He joined the RAAF and she became a VAD. They exchanged many letters.

Cast and Production Credits

Cast:

| KEN | Kevin Custerton |

| JOY | Juliet Charles |

| YOUNG KEN | Alex Ashcroft |

| YOUNG JOY | Stephanie Poon |

Production Team:

| TECHNICAL DIRECTOR | Raymond Simms |

| DIRECTOR | Cheryl Threadgold |

To read the radio play script, please click DOWNLOAD

To listen to the play, click on the arrow on the left below:

© Juliet Charles, 2018

*****************************************************************************************

- world war 1

All Over By Christmas

An original radio play written by Geraldine Colson

Synopsis

September, 1917: A family of parents and two children on a bush block outlying a city in Australia. They are sitting on a veranda on a very hot day, waiting for the postman, who delivers on horseback twice per week. They receive a letter which they eagerly go over and over, then a dust cloud appears through the heat of the afternoon.

Cast and Production Credits

Cast:

| MUM | Lynda French |

| DAD | Steve Morris |

| ANNE | Rebekah Philipson |

| DAVIE | George Klesman |

| POSTMASTER | Kevin Custerson |

Production Team:

| TECHNICAL DIRECTOR | Raymond Simms |

| DIRECTOR | Cheryl Threadgold |

To read the radio play script, please click DOWNLOAD below:

To listen to the play, click arrow on the left below:

©Geraldine Colson, 2018

*****************************************************************************************

world war 1

The End of the Red Baron

An original radio play written by Geraldine Colson

Synopsis and Historical Context

A one-act play for radio depicting the first burial of the famous First World War German fighter pilot and hero, Baron Von Richtofen, known universally as the ‘Red Baron’. The Red Baron caused the deaths of well over a hundred allied pilots, the highest number of recorded deaths by one pilot in WW1.

Burial of Baron R.M. von Richtofen, 1918 (Pictures Collection, State Library of Victoria H37629)

When he was finally shot down over allied territory in France in 1918, the Australian Air Force recovered his body and arranged a military funeral. Some of the phrases used in this play are actual comments by journalists of the day. A film was made by an on-looker at the cemetery which shows the burial and the ceremony accorded to the Red Baron by the Australians (available on-line).

The people in the small village close to where his plane came down were recorded as being extremely angry about the honour given to the German pilot. They tried to desecrate the grave but did not succeed in removing the body.

The Red Baron’s remains were later transferred to a military cemetery in Germany.

Cast and Production Credits

Cast:

| COLONEL | Kevin Custerton |

| FIRST OFFICER | Alex Ashcroft |

| SECOND OFFICER | Stuart Anderson |

| SERGEANT | Steve Morris |

| MADAME DUBOIS | Geraldine Colson |

Production Team:

| TECHNICAL DIRECTOR | Raymond Simms |

| DIRECTOR | Cheryl Threadgold |

To read the radio play script, please click DOWNLOAD below:

To listen to the play, click on the arrow on the left below:

©Geraldine Colson, 2018

*************************************************************************************

- world war 2

Evening in Paris

A radio play by Norah Dempster

adapted from a short story by Michelle Deans

Synopsis

In 1941 two Australian farm boys sign up for war service. Their mateship holds and they become Japanese prisoners-of-war. It is then that the true meaning of humanity shines through.

Evening in Paris by Michelle Deans is based on the true story of Stanley Marchbank (Australian Army Number VX 64139). The copyright of which is held by Michelle Deans.

Cast and Production Credits

Cast:

| PEGGY | Alana Spencer |

| STAN | Justin Keyt |

| JIM | Stuart Anderson |

| ARMY SERGEANT | Kevin Custerson |

| NED | Alex Ashcroft |

| JAPANESE GUARD | Stuart Anderson |

| RADIO ANNOUNCER | Angela Norris |

Production Team:

| TECHNICAL DIRECTOR | Raymond Simms |

| DIRECTOR | Cheryl Threadgold |

To read the radio play script, please click DOWNLOAD below:

To listen to the play, click on the arrow on the left below:

©Norah Dempster, 2018

***************************************************************************************

world war 1

When Frank Returns

An original radio play co-written by Jan Storey & Joy Meekings

Synopsis

It is November 1918 and the Germans have surrendered. Lily and her best friend Clara are worried they will be spinsters as so many young men have died. Private Frank is promised to Mary, Lily’s older sister. But, perhaps when he returns from service he may find the beautiful, younger Lily irresistible.

Cast and Production Credits

Cast:

| NARRATOR | Angela Norris |

| LILY | Jess Hickey |

| CLARA | Jessica Every |

| MARY | Alana Spencer |

| PRIVATE FRANK | Stuart Anderson |

| DR. BARRATT | Kevin Custerson |

Production Team:

| TECHNICAL DIRECTOR | Raymond Simms |

| DIRECTOR | Cheryl Threadgold |

To read the radio play script, please click DOWNLOAD below:

To listen to the play, click on the arrow on the left below:

©Jan Storey and Joy Meekings, 2018

***********************************************************************************

world war 1

For God, King and Country

An original radio play written by Jan Storey

Synopsis

It’s 1917 and the conscription referendum debate has turned bitter and divisive. John Hunt is in favour of conscription but his wife, Alice, is fiercely opposed. Their eldest son, Fred, has been injured on the Western Front and Alice is determined to stop their youngest son, Harry, from being conscripted. Will Harry be forced to enlist and will Fred survive the war?

Image Credit: Keith Tarrier/ Shutterstock.com

Cast and Production Credits

Cast:

| ALICE HUNT | Lynda French |

| JOHN HUNT | Kevin Custerson |

| HARRY HUNT | Ollie Culshaw |

| NARRATOR | Cheryl Threadgold |

| SERGEANT | Steve Morris |

Production Team:

| TECHNICAL DIRECTOR | Raymond Simms |

| DIRECTOR | Cheryl Threadgold |

To read the radio play script, please click DOWNLOAD below:

To listen to the play, click on the arrow on the left below:

©Jan Storey, 2018

***************************************************************************************

world war 1

Two Towns, One Family

A creative interpretation based on documented history

by Cheryl Threadgold

Synopsis

In May, 1918, six months before the Armistice on 11 November, Australian airman Lieutenant George Robin Cuttle MC came under fatal attack during a bombing mission behind enemy lines near Caix, ten kilometres from Villers-Brettonneux.in northern France. Driven by love and loyalty, Robin’s family members in country Victoria were determined to find the wreckage of his plane. In 1984, the towns of Villers-Brettonneux in France and Robinvale in Australia, became twinned. The strong connection between the two towns is a fine tribute to the heroism of men such as George Robin Cuttle and his fellow allied servicemen.

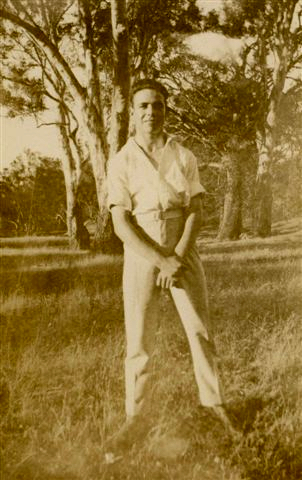

Image: Lieutenant George Robin Cuttle MC (Robinvale Regional War Memorial website)

Cast and Production Credits

Cast:

| FRENCH TEACHER | Geraldine Colson |

| STUDENT | Rebekah Philipson |

| NEWSREADER | Alex Ashcroft |

| BERNIE | Ollie Culshaw |

| LADY TOWNSPERSON | Lynda French |

| BRITISH AIRMAN | Alex Ashcroft |

Production Team:

| TECHNICAL DIRECTOR | Raymond Simms |

| DIRECTOR | Cheryl Threadgold |

To read the radio play script, please click DOWNLOAD below:

To listen to the play, click on the arrow on the left below:

©Cheryl Threadgold, 2018

***************************************************************************************

STORIES

Few escaped the destruction of the Great War

by Martin Curtis

What began as the Great Adventure maimed and destroyed a generation as Martin Curtis writes in an overview.

ON Monday November 11, 1918, after 1559 days of fighting, Germany capitulated and signed an armistice that would bring the calamity of World War I to an end.

The end of what became known as the Great War was greeted with jubilation. But Australia had paid a staggering price. From a population of just under five million, more than 416,000 men had enlisted. More than 60,000 Australians had been killed and 156,000 wounded or taken prisoner.

To put it another way, for every five that had gone away only four would return. Three of the original five would return sick, wounded or injured.

Long after their return many continued to deal with physical and psychological injuries and many women had to assume the financial burden of caring for families without an income-earning husband.

The “war to end all wars” changed Australia irrevocably.

Many believe Australia came of age during World War I. Its fighting men certainly earned a reputation for courage and bravery. And Australian military commanders like John Monash showed a compassion and interest in the welfare of the men under them that was lacking in many British officers.

But the legacy of broken bodies, broken hearts, widowed women, grieving mothers and fathers, and fatherless children hit Australia hard. A generation paid a high price for assisting Britain and its Allies defeat the German military machine.

WHEN the First World War began on August 4, 1914, Australian men and boys volunteered to join the fight – out of a sense of duty, and a chance to experience the world beyond our shores.

Australia might have been tucked away at the bottom of the world, but as a British dominion it pledged full and immediate support, just as Britain had done for its ally Belgium after it was invaded by Germany.

Age-old grievances, territorial disputes and petty jealousies over colonial empires had been held in check by a complex set of European treaties and alliances. The spark that lit the fuse was the assassination of the heir to the Austro-Hungarian throne by a Serbian nationalist. The declaration of war by Austria-Hungary on Serbia in retaliation for the assassination of Archduke Franz Ferdinand and his wife brought the major powers into the dispute. Russia pledged support for Serbia, Germany for Austria-Hungary and later Turkey and Bulgaria sided with Germany.

Britain declared war on August 4, 1914, after German troops invaded Belgium on their way to the prizes of Paris and the English Channel.

Anzac Head Quarters Gully, Gallipoli 1915 (Pictures , State Library of Victoria, H 38809)

BY 9am on August 5, men were already lining up at recruitment centres around Australia, offering themselves for God, King and Country. Around the enlistment depots and drill halls crowds gathered to cheer the men who answered the call.

Men like 26-year-old Edwin Bennett Spargo of East Malvern who enlisted eleven days after the declaration of war and became part of the 6th Battalion, one of the Victorian units that fought its way to the front line at Gallipoli on the first day, Sunday April 25, 1915.

Before he was killed in a dash at one of the well-defended Turkish positions on August 7, – over a cricket-pitch sized No Man’s Land – Lieutenant Spargo wrote to a friend in East Brighton likening the cliffs at Gallipoli to the cliffs at Red Bluff near Half Moon Bay. He wrote “these sandy bluffs are exceedingly difficult to climb and should be easily defended. In fact it looked the worst part of the coast to attack … We had to land in water up to our waists, but the sea being as smooth as glass this was no inconvenience … We were climbing up hill, into valleys, up again, through tangled undergrowth and low scrub, almost too steep in places to climb, and where we could (climb) only in single file.”

He described his company’s approach to the front line at Plateau 400: “What does it feel like? Imagine what a beehive sounds like when it is disturbed – buzz, buzz and zip, zip and ping, ping. But it is marvelous how used one gets to fire. We soon learn that the bullet we hear does not matter, as it has passed.”

Spargo was hit in the chest by a bullet on the first day of fighting, but was back on the front line for the August offensive.

Spargo was single, a clerk, and his educational qualifications were given as “junior public: University of Melbourne.” He had served three years in the City of Melbourne Infantry militia and was made Lieutenant on the basis of his militia experience.

A court of inquiry found Lieutenant Spargo was killed in action in the assault on German Officers’ Trench on August 7, but his body was never recovered. According to one report in his file he may have been taken prisoner. He does not have a grave in any of the war cemeteries at Gallipoli.

AS Christmas 1915 approached the Australian troops had left Gallipoli but the war was far from over, as the optimists predicted. Instead the war mired in the knee-deep mud of the Western Front and the casualties mounted for little gain.

By the second anniversary of the war’s start the home-front mood was sombre with any thought of an easy victory long faded. Australia’s forces, still new to the Western Front, had already been decimated in two bloody battles – at Fromelles in northern France and at Pozieres in the Somme Valley to the south.

Fromelles remains the most expensive battle in Australian war history in terms of lives lost in a 24-hour period. Almost 2000 died and more than 3500 were wounded.

At Pozieres, where fighting raged back and forth, there would be a massive 23,000 Australian casualties, including 6800 dead, in a series of attacks under almost constant bombardment.

As the third anniversary of the war’s start arrived, British and dominion troops were embarking on the eight weeks of the Third Battle of Ypres, a strategic Belgium town that had already been fought over in 1914 and 1915.

The ambitious British plan was to split the German line and drive the enemy back to the North Sea – but the offensive literally bogged down in mud and blood as a series of battles – Menin Road, Glencorse Wood, Polygon Wood, Broodseinde Ridge and, finally, Passchendaele – brought huge losses for little reward.

By April 1918, as the third anniversary of the Gallipoli landing was dawning at home, Australia’s soldiers on the Western Front were involved in what would be one of their greatest triumphs. In March the Germans had unleashed a series of massive attacks across Europe as the war’s fate hung in the balance.

From early April, Australian troops had been involved in what became an on-going battle for the French town of Villers-Bretonneux, which stood in the way of the Germans taking the city of Amiens, a strategic prize.

At Dernancourt, a sector of Villers-Bretonneux, the Australians held the line until they were relieved by British troops. But the Germans regrouped and in the ensuing battle, involving tanks on both sides, they took the town.

Immediately, Australian and British troops launched a surprise counter attack, the Australians closing under darkness to drive the enemy from the town and nearby woods. All up, they lost 1200 men but the enemy advance was halted.

French children in August 1919 tending the graves of Australian soldiers killed in battle at Villers-Bretonneux in August 1918 (Australian War Memorial, E 05925)

Ever since, Australia and its soldiers have held a special place in the hearts of Villers-Bretonneux’s citizens. After the war, donations raised by Victorian children helped rebuild the town’s school, called Victoria school, where an inscription reads in part: “May the memory of great sacrifice in a common cause keep France and Australia forever in bonds of friendship and mutual esteem.”

By Sunday August 4 1918, the fourth anniversary of the war’s commencement, Australian troops were part of an Allied push that increasingly had the Germans under pressure after two high-risk attempts to advance on Paris had failed. In July the Australians, under the command of their own Lieutenant-General John Monash, took the northern French town of Hamel using an innovative combination of infantry, artillery, tanks and aircraft that undoubtedly saved a considerable number of infantrymen’s lives.

In August, supported by newly arrived American troops, they took the high ground of Mont Saint-Quentin, overlooking the Somme River, and the nearby town of Peronne in a campaign that saw hand-to-hand combat.

In September they would breach the Hindenburg Line, Germany’s key fall back position behind its increasingly fragile frontline. The end of the war was near.

MOST Australian towns and suburbs have a memorial to the soldiers who served in the Great War. Many list members of the same family – brothers, cousins and uncles – who did not return. It’s said that in some country towns there weren’t enough young men to field a football team for several years after 1918.

In the Bayside area, there are Avenues of Honour in Sandringham, Hampton, Black Rock and Brighton while the Green Point Memorial at Brighton Beach honours soldiers with connections to the local area. Researchers list 93 men from the district who died at Gallipoli alone.

Like other housing subdivisions in the 1920s, streets in the Castlefield housing estate off South Rd in Hampton were named after WWI battlefields. The streets were named after the battles at Passchendaele, Amiens, Rouen, Lagnicourt, Avelin, Villeroy and Hamel. Imbros St was named after the Greek island where Australian and British wounded were taken off Gallipoli.

Important and enduring as these monuments are, it’s been the words of poets like A.D. Hope, Wilfred Owen and John McCrae who have seen through the fog of war. No triumphalism or myth-making here. Just the shocking reality of young men’s bodies torn apart by bullets and shells.

During the early days of the Second Battle of Ypres (1915) a young Canadian artillery officer, Lieutenant Alexis Helmer, was killed by a German shell. He was serving in the same Canadian artillery unit as the Canadian military doctor and artillery commander Major John McCrae. As the brigade doctor, John McCrae was asked to conduct the burial service for Lieutenant Helmer. Later that evening McCrae wrote ‘In Flanders Fields’.

In Flanders fields the poppies blow

Between the crosses, row on row,

That mark our place; and in the sky

The larks, still bravely singing, fly

Scarce heard amid the guns below.

We are the Dead. Short days ago

We lived, felt dawn, saw sunset glow,

Loved and were loved, and now we lie

In Flanders fields.

Take up our quarrel with the foe:

To you from failing hands we throw

The torch; be yours to hold it high.

If ye break faith with us who die

We shall not sleep, though poppies grow

In Flanders fields.

Sources

As Rough as Bags: the History of the 6th Battalion: Ron Austin 2005

The Official History of Australia in the War of 1914-18: Charles Bean 1941

The Great War: Les Carlyon 2006

The Wounded Warrior and Rehabilitation (including the history of No 11 Army General Hospital Caulfield): Bruce Ford 1996

The Fallen Diggers from Bayside, Victoria: Sandringham and District Historical Society 2015

Australian Associated Press War Stories Project 2016

The Australian War Memorial Canberra

©Martin Curtis, 2018

**********************************************

A Farewell to Arms 1918

by Martin Curtis

Harry Dodd’s role in the war to end all wars ended with the explosion of a shell that landed near him in the assault on Mont St Quentin on the afternoon of Sunday 1 September 1918.

In the grim humour of the London hospital ward where he ended up ¬– and with talk of a ceasefire on everyone’s lips – he joked that he’d already been disarmed and would soon be going home.

The same couldn’t be said of Hawkes and Jones. They were dead in a sugar beet field. ‘Known unto God’ was how the officials phrased their whereabouts, which meant Hawkes and Jones might be buried in a shell crater on the battlefield. Or bits of them might be.

‘Count your blessings’ the survivors said to one another.

A month later the German army was in retreat. Seventy-two days later it was official. The whole world would disarm. A peace plan was announced.

The night of the Armistice Harry got drunk with the other patients at the London rehabilitation hospital. The nurses and doctors went to celebrate at Trafalgar Square leaving the melancholic patients to ponder their fates.

The men in the grim circle felt a shift in their understanding of the universe that night. The war was over for the able-bodied who could celebrate, resume their lives, their jobs, their roles as sons, husbands, and fathers.

But what about the blind wheat farmer from Ararat, the man in the mask missing his jaw, the lung damaged bricklayer from Manchester, and Harry Dodd, the axeman from Jacksons Track who could fell five Mountain Ash trees in an afternoon if the timber mill at Warragul ordered them for the next day.

What was the peace plan for a one-armed axeman?

©Martin Curtis, 2018

*************************************************

The Two Poppy Ladies

by Norah Dempster

It all started with a poem written more than a hundred years ago.

A Canadian medical officer and writer, Lt. Col. John McCrae conducting a friend’s burial during the Second Battle of Ypres in 1915 wrote the poem entitled “We Shall Not Sleep” or “In Flanders Field”.

The last stanza read:

The torch; be yours to hold it high.

If Ye break faith with us who die

We shall not sleep, though poppies grow

In Flanders fields.

The devastating warfare and makeshift graves on the Western Front battlefield resulted in churned soil that fertilised the seeds of the wild red poppy, Papaver rhoeas. In what we can imagine was despair McCrae tossed the written words away. A fellow officer, and his name does not seem to be commonly recorded, picked the poem up and it was published in Punch magazine 8 December, 1915.

And that is where the two women came in, one American and one French. We don’t know for certain if they knew each other well, but we do know both women were active at the American Legion Convention in 1921 when it was decided to make the poppy a national symbol to raise funds for war veterans and their families.

The American woman, professor and humanitarian Moina Michael, a volunteer at the New York YMCA, read McCrae’s poem in a Ladies Home Journal that was casually placed on her desk. She felt so moved that in what she later called ‘a full spiritual experience’, she wrote a response on the blank side of a yellow envelope. She called her poem “We Shall Keep The Faith.”

We caught the torch you threw

And holding high, we keep the Faith

With all who died.

And with this pledge Moina Mitchell made a vow ‘I shall always wear a red poppy.’

She went out, bought a bunch of poppies to display, and when some conference delegates at the YMCA responded with ten dollars to say thank you for her efforts to brighten up the place at her own expense, she bought artificial silk poppies, wore one, and gave the others out to the conference delegates. She saw this as the first poppy sale and from then on campaigned tirelessly at her own expense to make the poppy a national remembrance symbol.

The Frenchwoman, Madame Anna E. Guérin, known as the Poppy Lady from France, an inspiring teacher and international public lecturer had frequently spoken of the needs of war orphans in France. After the Convention she began production of fabric poppies in French orphanages. She sent ambassadors across the world, including to Australia and New Zealand, to speak to groups and organisations to encourage them to adopt the symbol and buy the handmade red silk poppies.

In 1921, the Australian forerunner to the RSL (the Australian Returned Soldiers and Sailors Imperial League) imported one million silk poppies and shared the sale proceeds between a French Children’s charity and the League’s own welfare work.

In the same year in New Zealand the ship carrying 366,000 poppies from France arrived too late for Armistice Day. The New Zealand Returned Soldiers Association decided instead to sell the poppies around the anniversary of the Gallipoli landing 25 April, in 1922. In New Zealand the wearing of the red poppy is still associated with Anzac Day.

In 1921 the new Royal British Legion ordered and sold nine million poppies on Armistice Day.

The thousands of red flowers that bloomed in Northern France and Belgium during World War One came to be seen as symbolising the blood of fallen soldiers. Poppies are planted in memorial parks as perennial reminders of those who sleep under the battlefields. Poppies are placed beside names as a personal tribute in Memorial Rolls of Honour. The funds raised from their sale continues to help veterans and their families from all wars. We should also remember the Two Poppy Ladies for their inspiration and dedicated work.

Sources:

American Legion Auxiliary, Fact sheet: https://www.alaforveterans.org/

Australian War Memorial: https://www.awm.gov.au/

Commonwealth War Graves Commission: https://www.cwgc.org/

Madame Guerin: https://poppyladymadameguerin.wordpress.com

New Zealand History: https://nzhistory.govt.nz/war/anzac-day/poppies

The Great War 1914-1918: http://www.greatwar.co.uk/

The Poetry Foundation: https://www.poetryfoundation.org/

Poem Hunter Australia: https://www.poemhunter.com/

©Norah Dempster, 2018

*************************************

A Story Told

by Colleen Dewis

This is a story told to me by my mother. It’s a story about how her family responded to and was affected by the 1914-18 World War.

My grandfather, who died before I was born, migrated from Yorkshire to Australia in the late 1860’s.

He was granted land in the Hunter Valley NSW where he established mixed farms and a vineyard.

He and my grandmother raised a family of five sons and seven daughters there. My mother was their last child born.

Their second son, Lyndon who was born in 1887, at the age of 21years, joined the NSW Mounted Police Unit which had been established to protect travellers, capture escaped convicts, and fight indigenous Australians.

Other members of the family were engaged in work on the farm producing food for the rapidly expanding population in the Hunter Valley where coal was being mined and exported from the harbour in Newcastle.

When WW1 broke out the family supported the war effort in many ways. My grandfather raised funds and built a community hall where people gathered to work on various projects to support the soldiers fighting overseas. Many local men and boys had enlisted and were engaged in fighting overseas.

Men marching in Broken Hill after the White Rocks attack (State Library of South Australia PRG280/1/33/163)

Lyndon, as a Mounted Policeman, had been posted to Broken Hill during the miners’ strike in 1909, which had resulted in a ‘Lockout’ lasting five months. This required police reinforcements to be sent to the town to deal with ongoing riots during this period. Lyndon remained stationed in Broken Hill from 1909 till the end of the 1914-1918 war.

On New Year’s Day 1915, at 10 am, Broken Hill was the scene of the only enemy attack on Australian soil in WW1. This was just four months before the Anzacs fought the Turks at Gallipoli. A Silverton bound train was fired on by two men hiding in an ice cream cart and flying the Turkish flag. The train was carrying more than 1200 picnickers from Broken Hill to Silverton.

It had been a tradition in the mining town to hold a New Year’s Day picnic for the whole community and to travel by train to Silverton, a few miles away. The destination was a popular area along a shady creek. For this special occasion the iron ore wagons were hosed out and seating installed to transport the picnickers with their hampers to celebrate this annual event.

As a result of this surprise attack many people were wounded and in total there were six deaths, including the two attackers. The two turbaned attackers fled to a rocky outcrop just outside the town and were pursued by the police and militia. A gun battle lasting a few hours was fought there and finally the two attackers were shot. One died at the scene and the other died after being taken to hospital. Letters left behind by the two Muslim Afghans revealed they were responding to the Turkish Sultan’s jihad against all unbelievers as Turkey was then at war with Australia. They had planned to first shoot the operators of the train creating a ‘runaway’ train which would cause the deaths of all the train passengers. They intended to die as heroes of the jihad.

In 1918 the good news of the announcement of the signing of the Armistice and the end of the war was a cause of great euphoria and celebrations in the Hunter Valley community. There was also mourning for the local boys and men who would not return.

There was more good news for the family, besides the end of the Great War. Lyndon was on his way home from Broken Hill for some leave, before taking up his next posting which was to be in Sydney. This was an exciting time for my mother as she was just a baby when Lyndon left for Broken Hill.

While Lyndon was home on leave he became engaged to be married to his childhood sweetheart. This was a reason for another celebration and the Community Hall was put to good use again; this time with speeches, music and dancing.

After his period of leave Lyndon rejoined the Mounted Police unit in Sydney where his role was to patrol the wharves as the troop ships arrived back home. Unfortunately, the ships brought back not only the soldiers but also the deadly Spanish ‘Flu. In NSW alone approximately 6,000 people died due to this epidemic. Lyndon was one of the many who contracted the Spanish ‘Flu and he died in Sydney in 1919.

Because of this story told to me by my Mother, when I think of WW1 and the Armistice, I always think of two much-loved and admired members of my family whom I wish I’d been able to meet.

©Colleen Dewis, 2018

********************************************

A Victory

by Geoffrey Dobbs

Shortly before my grandfather died I called in to see him on my way back from school. I pressed the doorbell for as hard and as long as I dared. He was partly deaf, had hearing aids but hardly ever used them. He was very sick, we knew that, and I was secretly afraid of finding him dead on my own.

But the door screeched open and there he was: tall, stooped, all bones and sharp edges; a ragged cardigan hung from his shoulders like a poncho and old striped shirt billowed out over his grubby brown slacks. His long, thin white face, greyed with stubble looked down at me, puzzled. ‘Yes?’ He asked, croakily. I stared up at him for what seemed minutes, awaiting recognition that wasn’t forthcoming.

‘It’s me, Alan,’ I said finally and a thin smile crept across his face.

‘Of course it is, come in son.’

The house smelt of stale cooking scents, old clothes, faded leather and a miasma of ancient dust. I felt it was the smell of trapped time. He shuffled over to the table in the centre of the dining room and pulled out a chair for me.

‘Sorting out stuff,’ he muttered. An old blanket covered the table and heaped together in the centre was a collection of disparate objects: battered books, old tobacco tins, a large black-handled pocket knife, an old leather-bound notebook, his WW1 medals and slightly to one side and gleaming in the light, a gold ring.

‘Dunno what to do with it all. Don’t suppose you’ll want any of it. Put it in the bin I guess.’

‘But Granddad,’ I remonstrated ‘your medals … they’re priceless, of course we’ll want to keep them. I know that Dad will want them. You can’t just throw them away.’

He gave me a bleak smile. ‘They’re nothing special, I wasn’t a bloody hero. Everyone got them. But if your Dad wants them, he can have them—they’ll be yours one day then.’

He reached over the table and picked up the ring, placing it in the palm of his hand. I saw that it was a wide band of gold, slightly deformed with an embossed lozenge shaped shield. Then he closed his hand over it and stared into space.

‘You’re not going to throw that away too are you Granddad?’

‘Like it do you?’

He put the ring back on the table and leant back on his creaking chair.

‘I was a flier, you knew that didn’t you?’ I nodded. That was in fact all that I knew about my grandfather’s wartime life for he never spoke of it and as far as I knew he never took part in any ANZAC Day marches or any reunions.

‘November 1918, the fourth to be exact,’ he opened the leather-bound notebook and flicked through its yellowing pages. ‘Yeah, the fourth. We were advancing by then; the Germans were collapsing and we knew it would soon be over. There were rumours about an armistice but the fighting went on just the same. I’d been at the front for just a couple of months, flying a Sopwith Snipe. I’d been in a few dogfights, fired off God knows how many machine gun rounds, done a bit of strafing and bombing but as far as I knew I hadn’t brought down one enemy plane. Everyone else seemed to have one or more crosses painted on their planes but not me. And I badly wanted to get a Hun before it was all over.

‘Well, that day I got my chance. Two of us were sent out on a reconnaissance flight to see if the Germans were still occupying a hill ahead of the British advance. We’d been loaded up with four 25 pound bombs: if the hill was occupied, we were to bomb any artillery positions we saw. But the other plane struck engine trouble and had to turn back so I was on my own.’

‘Were you scared?’ I asked him.

‘Scared?’ He laughed drily. ‘Too bloody busy to be scared. You had to fly those planes with every inch of your body. Brute strength. No autopilot. Watch your fuel gauge, watch the altimeter, watch your heading and keep a sharp lookout above, in front, behind, below. Even in dogfights everything happened so quickly you barely had time to get scared—unless you were in a steep dive with a Fokker on your tail. Then you could get scared and with good bloody reason.’

He paused and for a few moments flicked through the pages of the leather-bound book which I now realised must have been his logbook from fifty years ago.

‘It was a bright, sunny day,’ he continued. ‘Ahead I could see the smoke of the battle front and as I climbed up to 15,000 feet, I could see that the roads were chock-a-block with advancing troops, lorries and horses. Once I was past the battle front I dropped back down to below 10,000 feet again. I found the hill and circled around it as low as I dared.’

He gave a short, gruff laugh.

‘Well, it was occupied alright and by the time I’d confirmed that there were several bullet holes in my wings so I dropped the bloody bombs as quickly as I could, without really seeing where they went, climbed back up to a safe height and headed back. I was getting close to the airfield when I spotted anti-aircraft bursts and tracer ahead of me. I headed towards them and saw that what they were aiming at was a Hun fighter, a Pfalz.

‘Now, I knew that I should have gone straight back to the airfield and given my report but the Pfalz was a bloody tempting target. If it had been one of the new Fokkers I might have thought twice about tackling it. But a Pfalz, well, I reckoned I could deal with that. You see Alan, the Pfalz was a single-seater fighter the same as mine; well armed alright and fast, but not as fast as my Snipe or as manouevrable. The Snipe was one of the best fighter planes we had.

‘I had the engine at full throttle, going like the clappers, over 100 miles an hour. Well, that’s not much these days of course but it was pretty bloody fast then. The Pfalz was circling, maybe looking for targets on the busy roads below.

‘Best of all,’ he continued, ‘I was at about 7,000 feet and the Pfalz was below me, maybe at about 4,000 feet. You always tried to attack from above and behind. Dive down, get as close as you could and then take the shot. That’s what we used to say, you see ‘take the shot.’

He paused and picked up the pocket knife and the tobacco tin to demonstrate.

‘I went down in a shallow dive, like this, timing it so that I would have the Pfalz in my sights as it completed a turn. I bloody near missed him then because he suddenly started to climb but I managed to pull out of my dive fast enough to get him in my sights for about ten seconds and I gave him a short burst from the Vickers. Dunno if I hit him. He tried to zoom up above me so I banked really sharply like this—the Snipe was a bloody marvelous kite for that sort of manoeuvre—and followed him up at full throttle. I knew that I could climb faster than he could and I went straight past him as he did a half –roll out of his climb. I made a very tight turn out of the climb, so tight I thought the bloody wings might tear off, reckoned I could hear the struts and wires screaming. Then I dropped down on the Pfalz just as he was starting to climb again. This time I had him filling my sights head on for a good twenty seconds and I just kept firing. Reckon I must have fired about a hundred rounds into him. We were so close that we bloody near collided.

‘I thought I’d lost him because all of a sudden the sky was empty, no sign of him. Maybe I’d got him and he’d gone down I thought. I circled around, half expecting him to come at me from below. And then I spotted him. He was heading east, away from me. There was a long, thin trail of grey smoke coming from his engine and he going down slowly in a shallow dive. Well, I felt pretty bloody pleased with myself. I’d got my Hun.

‘Dunno whether I should tell you this … haven’t told anybody for over fifty years.’ He paused and looked closely at me for a moment.

Courtesy of National WWI Museum and Memorial, Kansas City, Mo., USA

‘Well, looked like the Pfalz was going for a crash landing. Then I thought what if he gets downed by ground fire? I’ll miss out on getting the credit. So I followed him down, throttling back until I could close in about fifty yards behind him. The smoke from his engine was drifting into my cockpit and I could smell the burning oil. He looked back at me once, or did I imagine that? Perhaps he knew what was coming or maybe he hoped I’d let him get down safely. I took my time Alan, waited until I had the Pfalz full in the sights and then fired. I saw bits flying off the tail and wings and I saw his head jerk back. Then there was a huge burst of flame from his engine and the Pfalz sort of flipped and then went straight down. We couldn’t have been at more than 2000 feet, if that, and by the time I’d circled back I could see black smoke and the flicker of flames on the ground below.’

He scrabbled around the table, found a half crushed packet of cigarettes and lit one with shaking hands. He held on to the match until it was flickering around his fingers.

‘D’you know what I felt?’

‘Excitement? Pride?’ I suggested.

‘Yeah. I reckon. And relief.

‘The next thing I knew, I was over the airfield. I realized then that the Pfalz must have been aiming for a crash landing there. Once I’d landed I was greeted with congratulations by everyone of course, except for the Intelligence Officer who gave me a right bollocking for not returning straight back with my report and leaving the Pfalz for others to deal with.

‘After I’d completed my report, a fellow pilot who had a motor bike suggested that we go and see the wreck. I was still “on a high”, as you would say, and the idea of securing a few souvenirs from my first victory was pretty appealing. So, after zig-zagging around a few muddy lanes lined with shattered tree stumps and scrambling around old shell holes we got to what was left of the Pfalz. It had crashed alongside a main road and was surrounded by a cluster of soldiers. They fell back sort of respectfully when we turned up and I really liked that! I was still in my flying gear so they quickly worked out that I must have been the one who brought it down. A young officer came up, saluted me and offered his congratulations. “We saw it all,” he said, ‘”good work. The pilot landed over there— oh, don’t worry he’s a good Hun, the best kind there is— a dead one.”

‘Now, I really hadn’t thought much about the pilot. Thought he’d have been burnt up with plane I suppose. And I can’t say I was that keen to go and look at him but the officer obviously assumed that I’d want to see the result of my handiwork and led me across fifty yards or so of mud to another group of soldiers. A few ran off when they saw us coming.

‘The pilot was lying on his back, arms flung outstretched, one twisted right around so that the hand was palm downwards. I noticed that the other hand which still had a glove on, was partly burnt as if he’d tried to beat the flames out. There was a sickening smell of petrol and of burnt flesh and leather. I didn’t understand at first; then I realised that he must have jumped from his burning plane. He must have been wounded, there was a hole in his shoulder, still bleeding, but he’d managed to jump. He was that desperate not to be burnt alive. His face was unmarked and I looked straight into his half-closed eyes. They were grey. I bloody near puked there and then but managed to hold it back. His body had already been stripped by souvenir hunters. His flying helmet, goggles, and one glove were gone; his flying jacket had been ripped open and that would have gone too if we hadn’t arrived.

‘The officer apologised explaining that he’d put a guard on the body but … “you can’t trust these chaps I’m afraid. They know it’s nearly over and are out after any souvenirs they can get. I’m afraid they’ve even taken his ID disc.” As he spoke, the officer grabbed at a soldier who was trying to slip away with the missing glove. He ordered the man to empty his pockets. The soldier wasn’t happy about it, I could tell that: he deliberately spat on the ground alongside the dead pilot before handing over a gold ring – this ring. “You’d better take it,” the officer said, “may help to identify him, if you can be bothered!”

‘Well, that was my souvenir young Alan. And as far as I know that was the only German I killed. I flew a few more patrols, without incident, and a few days later the armistice was declared. I got to thinking afterwards about what I’d done and I didn’t feel as proud of myself as I had at first. I got to thinking that if I’d let that German crash land his plane, he might have survived the war, like me.’

‘But surely you were just doing your job, your duty? Millions died in that war, you only killed one.’

‘Maybe Alan, but it didn’t seem like that, then or now. You see, I’d killed for the sake of it, for the sake of getting a cheap victory and a painted cross. That pilot wasn’t going to fly for Germany again, even if he survived the crash. Think about it son; if it hadn’t been for me he might be sitting down talking with his grandson, like me, right now. That’s the real tragedy of war, you know: you don’t just kill one man, you kill his children, his grandchildren, generations …’

As he finished his tale, my grandfather handed me the ring. He pressed it into my hand, closing my fingers over it.

‘I want you to promise to keep it safe, maybe even wear it when you’re older and I want you to pass it on to your own children, and tell them its story.’

A few weeks later my grandfather died.

That was over fifty years ago. I no longer have the ring. My eldest daughter has it now. She wears it on ANZAC Day and Remembrance Day, in honour of two young men who met in the skies above Flanders a hundred years ago; of one who lived and of one who died.

© Geoffrey Dobbs, 2019

*************************************************

Remembrance

by Geoffrey Dobbs

On 11th November 1918, as the bells of Shrewsbury rang out in celebration of the Armistice, a telegram arrived at the home of Thomas and Harriet Owen. It told of the death in action of their son, Wilfred, a week previously.

Owen would become the best known poet of the First World War. The unflinching realism of his war poetry and his personal bravery (he won a Military Cross) combined to make him an archetypal WW1 figure: disillusioned, compassionate, without hatred, yet committed to doing his duty and caring for the men under his command. Poems such as ‘Anthem for Doomed Youth,’ ‘Strange Meeting,’ and ‘Dulce Et Decorum Est’ are part of the English literary canon. Yet, we rarely hear them read at memorial services. Instead, we hear the solemn, words of the reverential ‘Ode.’ Perhaps this is not surprising. Memorial services tend to emphasise courage and sacrifice rather than the suffering and horrors of war. The military elements of these ceremonies, the precise marching, the smack of ordered arms, the polished bugle calls, the minute’s silence, the ‘Ode’ all combine to create an atmosphere of sadness and pride that is at once emotionally challenging and satisfying. We are moved and uplifted, feeling better about the dead and about ourselves. When the ceremony is held at a war cemetery the emotional impact is even greater.

But what would Wilfred Owen have thought about these ceremonies? Certainly he would have approved of the act of remembrance itself but I think the theatrical elements would have disgusted him. He would have wanted us to remember the horror and the futility of the war. I think too that he would have wanted us to share the transcendent compassion and forgiveness for the enemy so movingly expressed in ‘Strange Meeting’:

I am the enemy you killed, my friend.

I knew you in this dark: for so you frowned

Yesterday through me as you jabbed and killed.

I parried: but my hands were loath and cold.

Let us sleep now…

Wilfred Owen plate from poems (wikimedia.org/wikipedia/commons/thumb)

Now, a hundred years after the end of WW1, have we lost awareness of the realities of that war? Our ceremonies emphasise courage, mateship and sacrifice. Our memorials offer us the names of the dead but say nothing of how they died. In our war cemeteries disciplined lines of uniform headstones stand to attention on clean, clipped grass: all the brutal realities of battlefield death have been tidied away and sanitized. We are moved, as we should be, but shouldn’t we also be horrified? Perhaps those soothing, almost clichéd words of the ‘Ode’ should be accompanied by Owen’s ‘Dulce Et Decorum Est’ with its vivid, sickening description of a soldier dying from mustard gas.

If you could hear, at every jolt, the blood

Come gargling from the froth-corrupted lungs,

Obscene as cancer, bitter as the cud

Of vile, incurable sores on innocent tongues,—

My friend, you would not tell with such high zest

To children ardent for some desperate glory,

The old Lie: Dulce et decorum est Pro patria mori.

And, behind all the solemn rituals, behind the weeping, flag-shrouded ‘pilgrims,’ lurks a dark, uneasy question: where was the justification for this appalling human catastrophe?

This question demands to be asked; and to be answered with the same unflinching honesty of Owen’s poetry. Otherwise our acts of Remembrance will memorialise only palliative myths and the deaths of millions, from all sides, will remain meaningless.

WW1 was claimed to be the war that would end all wars; it didn’t. Honestly confronting its brutal realities and futility may help prevent us from being lured or pitched into other murderous and pointless conflicts. That, at least, might add purpose and practical meaning to our outpourings of emotion.

Quotations from ‘Strange Meeting’ and ‘Dulce Et Decorum Est’ are from The Collected Works of Wilfred Owen, Edited C. Day Lewis Chatto & Windus London 1984

©Geoffrey Dobbs, 2018

*******************************************

To the unknown Medical Officer……

by Helen Graham

Dear Sir,

You don’t know me, but I am very grateful for what you did during World War 1. To you it was a simple decision, but to my family, it one of great consequence.

What did you think when the tall, lanky country boy with the bright blue eyes stood, stripped to the waist, in front of you?

I understand you checked him thoroughly, probably impressed with his stature and his fitness. No obvious medical issues presented themselves on this handsome young man. Checking his paperwork, you noticed that he had given his age as 18. But, to your trained eye, there had to be a few more years before he would celebrate that birthday.

So, you questioned him. Did you notice the flicker of his eye when he told you he was 18? Did his face redden slightly, or did he shift his feet, indicators of perhaps a truth not being told? Did you have a son about the same age? Had you processed so many young men, the fittest and most able carriers of Australia’s future gene pool, that you instinctively knew that to send yet another young underage boy off to war was folly? Or had you seen the grief and damage caused by the never-ending list of casualties that came across your desk?

Whatever it was, you hesitated and then told him quietly, so as not to embarrass him, that he was to be deemed medically unfit to serve. The reason? Because he had rheumatic-prone joints and this would be exacerbated by time spent in the dreadful, muddy trenches of France.

When the official paperwork arrived at his home, his mother was outraged that he had sneaked away to enlist, but grateful he had been rejected.

By the time he turned 18, World War 1 was over and the family and friends of the 60,000+ Australian dead were left to mourn. With over 150,000 injured, the impact on families, friends, communities and our nation was profound. So many damaged men, husbands, fathers, brothers, sons, for whom life would never be the same.

But our family, by the stroke of a pen, was spared this suffering. Well not quite, because my father always regretted that he couldn’t serve his country, like all the other men he knew. When World War 11 started, he again tried to enlist, but was deemed an essential service worker and so was thwarted once more.

So, I grew up in a home headed by a father who was not damaged by the brutality of war.

By the way, he never did suffer from rheumatics.

To you, the unknown Medical Officer, I thank you.

©Helen Graham 2019

***************************************

Her Laugh broke the Silence

by Sue Hardiman

Her laugh broke the silence. Sitting around the family room on a long and sad day and suddenly my grandmother’s laugh broke the silence and she left the room to look for one of those manuscripts that sit better in the bottom drawer than in a bookshop.

Nana returned with a beautifully bound handwritten manuscript by her late husband, Poppa, and with encouragement from her children and grandchildren, she read some passages.

Poppa was a marvellous storyteller and a small child believes every word coming from a loved Poppa’s lips. However, many of the stories were just that – stories. But the stories Nana read to us on the day of Poppa’s funeral revealed the real man – the man whom most of his family did not know; some of his stories were unknown even to Nana.

German prisoners lined up before a British Intelligence Officer (Australian War Memorial, E00180)

We learnt that Poppa was an intelligence officer for the British army during the first World War and we learnt of the very real and dangerous risks he took to do his job properly. We heard of his loneliness. As an Intelligence Officer he could not confide in anyone – not even his much-loved English girlfriend. He had told us stories about his wounds and made the getting of these wounds sound very exciting and not at all dangerous. He told us how his arm was shot off and his long stay in hospital and being looked after by the pretty nurses, and what fun the soldiers had in hospital – pretty nurses everywhere. How wrong these stories were, but how right they were for his young grandkids. He wrote about his mates in the Intelligence Unit but never gave them names. His manuscript contained a copy of a letter from one of these mates and it must surely have brought tears to Poppa’s eyes – it did to ours when Nana read it out to us. This letter was addressed to Pop at his local Post Office and fortunately the staff managed to deliver the envelope containing this precious letter and two photographs – photographs he did not put in the family album.

Nana knew some of the story but Poppa had always told her the glamorous side of his life in the services. He had indeed played a real part in ensuring that Britain was not defeated. Badly wounded but not defeated (he was shot in his left arm and gangrene set in resulting in the arm being amputated at the shoulder). He wrote about the sadness war brings – sadness to all sides – and how in later life he felt that there were no winners in war. He wrote about the devastation and destruction of beautiful buildings and homes that bombs destroyed, the heartache that went with this, the breaking up of families

Nana was born in Australia to Australian parents and her family did not take an active role in the war. However, she understood Poppa enough to respect his silence about his war and she had never looked at his manuscript until the day of his funeral. Although his story brought lots of tears it also gave us lots of laughs. The family decided that day never to seek publication of this wonderful account but made a copy it for each member of the family, and returned the original to its rightful place, the bottom drawer.

© Sue Hardiman, 2017

*********************************************

Three Days a Second Lieutenant:

Jack Playne

by Martin J Playne and Christine J Playne

This is the story of a young engineer from Western Australia who patriotically enlisted to fight alongside his best friend at Gallipoli. John Morton Playne was born in England in 1883. The family decided to migrate to Australia in 1888, and start a new life. They settled in Albany, W.A. in 1888. John was always called ‘Jack’ by family and friends.

The Great Pyramid, Giza, Egypt (photo by MJ Playne 1962)

In 1902, Jack passed the cadets engineering exam in Perth, and along with his friend Geoffrey Drake-Brockman, he started his engineering training in the Public Works Department. The cadets spent their first year at the drawing board by day and the technical school in the evening. After the first year, they were transferred to operations in a railway camp. Drake-Brockman describes how he and his fellow cadets lived in similar camps, and carried out similar tasks, such as chaining, traversing, levelling, buggy driving, drafting and studying.

In 1907, the two young State-trained engineers were transferred to water supply, sewerage and drainage construction. It was busy time for them as Perth was expanding fast, and sewerage was being introduced. These were good years for the young men – they were based in Perth, socialised and played sport together. After this, the young engineers moved on to new projects surveying for the construction of new railways, particularly the trans-continental railway.

The Landing Place, Anzac Cove, Gallipoli, 1915 (Pictures Collection, State Library of Victoria H81.169/42 creator: CA Masters)

Then on 4 August 1914, England declared war on Germany. The young men volunteered to become soldiers in September 1914. They enlisted with the 10th Light Horse Regiment at Guildford, W.A., having passed the horse riding test and medical examinations. Jack had to practice long and hard to improve his limited horse riding skills. Each soldier had to donate a horse. During training in October and November, they shared a tent with eight soldiers and ate dixie stew three times a day. They completed their training at Rockingham on manoeuvres with the horses, often in darkness and at night – marvelling at the sight of 450 horses travelling at night. Drake-Brockman and Playne became close friends and were often detailed for special engineer duties. Drake-Brockman in his book ‘The Turning Circle’ describes this period of military training in detail, and goes on to say: ‘The Light Horse then had no sapper attachment. Together we made reconnaissances and maps for manoeuvres. Later, on the voyage to Egypt, together we lectured officers of the regiment on field sketching and map reading – our reward a drink in the officers’ mess.’

They sailed from Fremantle for Egypt on 15 February 1915, arriving at the port of Alexandria on 16 March. On disembarking, they travelled by train immediately for Cairo and to their training camp at Mena, within sight of the famous Sphinx and the Great Pyramid, which Jack and his friends enjoyed climbing. Soon their turn came to fight the enemy. They came ashore at Gallipoli on 21 May 1915. The Regiment took over a trench section, and manned the lines at Walker’s Ridge, Quinn’s Post, Pope’s Hill, Russell’s Top and Number One Outpost. Although Playne and Brockman did sentry duty in the trenches, the two were kept in reserve for special survey work.

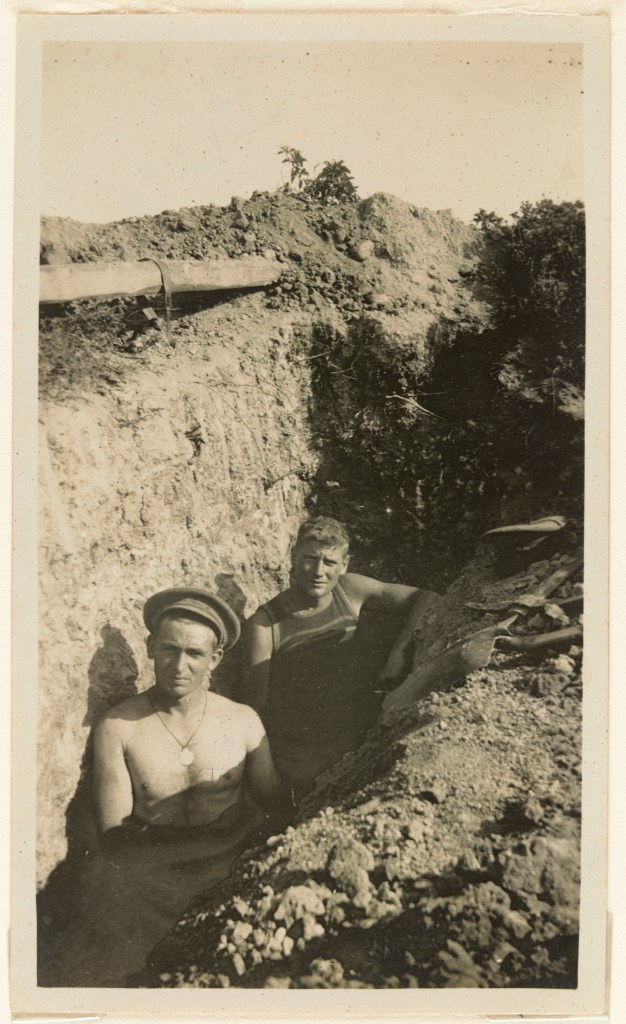

Digging trenches, Gallipoli, CA Master and comrade 1915 (Pictures Collection, State Library of Victoria H81.169/85)

In July as the fighting dragged on with its terrible loss of life, Playne and Drake-Brockman applied for commissions with the Australian Engineers and on 3 August 1915 were appointed as 2nd Lieutenants. That same day they said their farewells to the 10th Light Horse and were placed in charge of sections of sappers at Lone Pine, trenching and tunnelling. Their immediate task as Australian Engineers was to prepare trenches for an offensive. ‘The August Offensive’, as it was called, was to capture Turkish trenches at Lone Pine on 6 August. They succeeded, but it resulted in heavy casualties. The attack was to start at 0530am on 6 August 1915 and to be a diversion from a simultaneous new landing at Sulva Bay and other attempts to break out of the Anzac positions. The first jump out from multiple locations along the trenches included Jack Playne and his sappers. Their job was, when the Turkish trench was captured, to tunnel back towards their own trench. Geoff Drake-Brockman’s duty was to tunnel from their own trench and to meet up with Playne’s tunnel. Playne never signalled his arrival in the Turkish trench. He and his sappers had died in the fighting on that fateful day. Playne’s body and identity tag were found nine days later. His body was never recovered. He is memorialised at the Lone Pine Memorial, Gallipoli Peninsula, Canakkale Province, Turkey. He was one of 3268 Australian soldiers who fought on Gallipoli and have no known graves.

His former colleagues in the 10th Light Horse Brigade from Western Australia fared even worse. On the 7 August, they were ordered to attack at The Nek, already knowing they were following other regiments to certain death. Realising this, their commanding officer made attempts to halt the charge, but he was overruled by brigade headquarters. An estimated 234 young Western Australians were killed needlessly in this attack.

Soldiers’ Camp, Gallipoli 1915 (Pictures Collection, State Library of Victoria H42641/4)

Sources:

Australian Red Cross Society Wounded and Missing Enquiry Bureau files, 1914-18 War, 1DRL/0428, 2nd Lieutenant John Morton Playne, 2nd Field Company Engineers

Australian War Memorial, Private Record PR83/067. Four page letter dated 14/5/14 from Gallipoli of Lt Jack M Playne, 3rd ALH, AIF, to his father. AWM file 419/10/36 (incorrectly dated, must have been 24 May 1915)

Australian War Memorial, Australian Imperial Force Unit War Diaries, 1914-18 War, Engineers, AWM 4, Item 14/21/8, Title: 2nd Field Company, Australian Engineers, August 1915 (online http://www.awm.gov.au)

Beaumont, J., Broken Nation-Australians in the Great War (Allen & Unwin, Sydney NSW), 2013, pp124-137

Browning, N. and Gill, I., Gallipoli to Tripoli: History of the 10th Light Horse Regiment AIF 1914-1919, (Hesperian Press, Carlisle, W.A.) 2012

Drake-Brockman, G., The Turning Wheel, (Paterson Brokensha Pty Ltd, Perth, WA) 1960National Archives of Australia NAA B2455, Australian Imperial Force. Service Record (Attestation paper sworn on 9 Dec 1914, he enlisted at Guildford, WA on 25 Sep 1914. Medical examination, promotion, casualty form, letters concerning his death)

© Martin J Playne and Christine J Playne, 2018

************************************************

Desert Strike

by Kenneth Pryce Wilson

Forward by Juliet Charles

My father, Kenneth Pryce Wilson (Ken), applied for and was accepted into the RAAF. He trained first as a pilot and instructor at Wagga, then attended Officers’ School in Somers. He emerged with the rank of Flying Officer and on Good Friday, 10th April, 1941, set sail from Sydney Harbour.

He initially fought in the Middle East, and his first post was with a British Squadron – No. 14. He was the only Australian. During his time in the Middle East, he clocked up many hours piloting Ansons, Wirraways and Blenheims I, IV and V to name just some of the aircraft. He was involved in countless raids and “sorties” as well as training other young pilots in Blenheims and other aircraft.

After the Middle East he served in New Guinea, flying Beaufighters, which were nicknamed “Whispering Death”.

He achieved the rank of Squadron Leader during his years of service.

“Desert Strike” is one of many stories he wrote in later years about his experiences in the Middle East.

Kenneth Pryce Wilson 18/3/1916 -27/4/1996

Desert Strike

Ken awakened slowly and looked around the tent. The other four officers were stirring. It would be another cold day and the rest of the squadron – all pilots of Blenheim IV bombers – was on standby. For weeks they had been attacking targets behind German lines, ranging beyond Tobruk and Benghazi.

After they’d washed and dressed, the men wandered over to the cook tent and breakfasted on tinned bacon, biscuits and sweet tea – the same as every other day.

He was the only Australian in this British Squadron; his navigator was English and his wireless operator-rear gunner was Scottish. They’d crewed together months before at the final training school in Ismailia and had now clocked up 25 operational trips. The war in the desert was becoming more intense and casualties were mounting. He wondered what today’s target would be. After breakfast he and his crew walked to his Blenheim, and together with the ground staff, made his usual daily inspection. It was cold, but he was warm in his battle dress, scarf and fur-lined flying boots. He watched carefully as the armourers winched four 250 pound bombs into the belly of the aircraft. The bombs were fitted with extension rods to ensure explosion on impact with the ground – essential when bombing vehicle traffic on the road and armoured vehicles in the open desert. He then went to the Operations tent to discuss the day’s flying with the Commanding Officer (CO).

Buck was at his desk finishing the routine paper work which he loathed and usually left to his adjutant, Jock. Buck was a born operational pilot – absolutely fearless – and flew on every possible occasion. “We’re going to El Aguila,” he said. “It’s on again – a big tank battle in progress and our target is the supply units behind the battle. It’s a full-scale job. Three squadrons including the Free French Lorraine. We’re leading and you will fly No. 2. We’ll have a Hurricane escort – take off at 1200 hours.”

With a few hours to wait, he went back to the tent and prepared his equipment – flying helmet, revolver in holster and seat parachute. He wrote some letters home then sat in the Officers’ Mess tent with the other pilots.

The Intelligence Officer struck a gong outside the Operations tent, signalling the commencement of the operation. He joined the others gathered around a trestle table spread with maps covering the flight path. The briefing was detailed and covered the battle situation and enemy aircraft expected. Formation positions were allotted. As No. 2 to the CO he had to maintain a position on the CO’s starboard side, tucked in so tightly that the wings of each machine overlapped. On the port side, the leader of the next Vic1, No. 3, was in a similar position, maintaining his position “in the box” with his nose just under the CO’s tail wheel.

This basic Vic formation was repeated for as many planes as were flying. It was tight, giving mutual protection and allowing for accurate bombing of the desert road.

After briefing, he and his crew were driven to his aircraft. Following another look around, they boarded and prepared for take-off. Pre take-off drill and inter communication checks completed, they waited for the light-flare signal for take-off. He signalled his readiness, started the port engine and pressed the start button. The engine fired, hesitated and then ran steadily. He throttled back and started the starboard engine. After the engines had warmed sufficiently, he ran each one up in turn to full revolutions with the stick hard back and full brakes, then tested the magnetos2 for revolution performance. Satisfied, he taxied to the take-off point. The wheel chocks were pulled away, the locking pins removed from the undercarriage and after the wave from the ground staff he was ready. The CO’s plane moved forward and he fell into line behind him, all the other planes of the squadron following in their allotted places.

He put his plane into position and watched the CO. He pushed the throttles forward as he saw the CO’s plane move, and gathering speed, maintained his position. Tail up, full throttle, and they were air-borne. He breathed his usual short prayer, “Lord, bring us safely down.” The leading Vic turned across the landing ground, slowly gaining height. The following Vics took off in their turn and closed up. Soon they were in full formation and circling the landing ground. They continued to circle and climb as the other squadrons took off in turn and fell in behind. The Hurricane escort moved up alongside. The full formation of 36 planes was now heading west at 10,000 feet. The hard work of keeping perfect position in the formation occupied his full concentration, but out of the corner of his eye, he could see the Mediterranean, the fortress of Tobruk, and the desert stretching out on all sides.

An hour later, they were approaching the target area. Below in the desert, were the dust trails of hundreds of vehicles – tanks, cars, transporters, fuel lorries, all churning up the earth in a swirling pattern. Radio silence had been maintained throughout the whole trip, but now there was a sudden clamour from the navigators and gunners. “Enemy aircraft coming down.” He automatically edged his plane and hung on grimly, throttles opening and closing to maintain the correct distance. His left hand gripped the control column wheel like a clamp. He was too busy to be afraid. He saw the black form of a Messerschmidt 109 flash vertically past the CO’s plane and at the same moment, No. 3, the plane on the other side of the CO, burst into flames and fell away from the formation. What happened to it, he never found out. The formation continued to circle the battle area, and it was clear that in the mixed melee below, no target could be identified.